| About Us | Contact Us | Contact Database | Support Us |

- MANUAL-

Local Organizations managing Sustainable Energy

When new solutions are introduced, it is important that involved organizations,

companies, and users are able to handle the new tasks they get. Often

the best solution is to create a new local organization, formal or informal,

to handle some of the new tasks. This chapter gives an overview of some

of the most used and the most successful organizations and structures

to manage local sustainable energy solutions in South Asia.

4.1 Planning and implementation of RET projects by Grameen Shakti in

Bangladesh

Grameen Shakti (GS) uses short feasibility studies, reports from the

field to plan and implement its projects. In many cases, short duration

pilot projects are carried to test or fine tune an idea. For example,

before opening a unit office on a new site, GS carries out a short feasibility

study to find out the market potential of Solar Home Systems (SHSs) on

the new site and whether it would be financially viable to open a new

unit office there. Field staff focus on the following when carrying out

their analysis: (i) no possibility of grid coverage in the near future

(5 to 10 years); (ii) interested of people in SHSs; (iii) purchasing

capacity of prospective buyers/customers; and finally (iii) total demand

to ensure a operation of unit office on a sustainable basis, i.e. there

would be at least 350 customers over the next three years.

Over the years, GS has developed in-depth understanding of the rural

market. This has been achieved through continuous gathering of data through

its wide network of field staffs and unit offices. These extensive data

helps GS to develop new products and programmes as well as fine tune

its existing programmes. For example, one of the surveys carried out

by GS, showed that there was a potential market for new devices such

as DC-DC converters, safety devices for black & white television

sets, solar powered mobile phones, micro-utility models etc. Later, GS

developed these products in response to client needs.

4.2

Communities & Women

Involvement in RET implementation by GShakti in Bangladesh

Involvement of the local community is vital for the successful operation

of Grameen Shakti (GS) renewable energy programme. Right from setting-up

the GS gives local communities control over solar installations in their

areas. This is achieved by GS working with teachers, community leaders

and elected officials, who are explained the benefits of the solar home

systems to the people they represent. Another important aspect of the

local involvement is the manufacture, repair and maintenance of solar

accessories close to the communities that are served by GS, by people

who are familiar with their needs.

The main focus of GS is women who are always involved with its various

programmes. For instance, women from end-user families have been trained

as technicians by GS staff so that they can take care of the day-to day

maintenance of their Solar PV systems.

From experience GS has learnt that it is more viable to train women than

men as the men are in jobs outside their homes. Moreover, women technicians

would find it easier to enter the ‘End Users’ homes when

the only members available are women-folks as their men-folks are working

outside their village. GS has also facilitated empowerment of women by

providing them opportunities to earn their livelihood through business

ventures such as solar powered mobile phones, home based poultry, handicraft

businesses etc .

4.3 Trading Methods and Organizations

in Sri Lanka

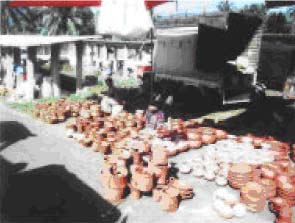

Sri Lanka Stoves Program has two different routes for dissemination of

stoves:

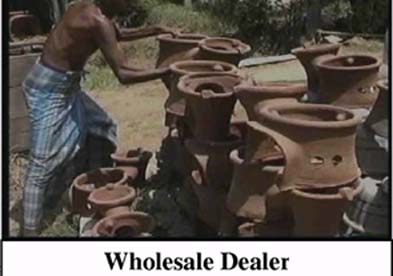

1. Commercial Route: In the commercial route there are 185 potter families

distributed in 17 districts producing over 25000 stoves monthly. However

almost 50% of the production is concentrated in one village consisting

of 29 potter families who produce stoves in large quantities.

A survey revealed that nearly 65% of stoves sold to the traders are on

spot cash 31% who had received a cash advance before and 3% were sold

on credit. Many of the producers have regular dealers. However the producer

dictates the terms since demand far exceeds the production level.

Modes of selling between producers and traders can be classified

as below:

Modes of selling between producers and traders can be classified

as below:

-

Producers sell to wholesale dealers visiting the site.

-

Producers themselves deliver to outside retailers directly.

-

Producers themselves deliver to wholesale dealers outside.

-

Small producers sell in the village.

-

Producers sell to the producer coop society.

-

Producers sell to Producers who are also wholesale dealers.

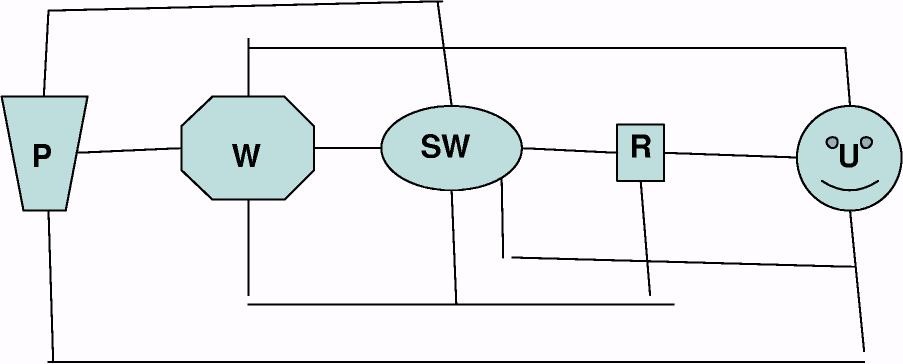

P= Producer

U= User

W= Wholesale Dealer

SW= sub wholesale dealer

R= Retailer

In the case of small scale isolated producers where traders do not call

over, the stoves are the taken to the village fair and sold directly

to the users. In places where the commercial route is operating stoves

are bought from retail shops. However there are also street vendors

who deliver the stoves to the user.

2. Dissemination Route: While the commercial route is mainly a traders

affair, in the dissemination strategy, NGOs establish a revolving fund

to facilitate

the users who live in isolated areas who have no access to the commercial

route to purchase stoves which are bought by the NGOs from either producers

or traders and distributed to the users. Users pay the cost of the stove

in installments. In the dissemination route, a small profit derived by

selling the stoves is used to enhance the revolving fund to reach a wider

group of users. If funds could be obtained from donors users are given

stoves at subsidized price.

4.4 Self-Help Groups of Women’s for the promotion

of Hh Biogas Plants in India

AIWC had been implementing household biogas plants, under the centrally

sponsored, National Project on Bio-Gas Development (NPBD) of (MNES),

Govt. of India, since 1994, as one of the Nodal Agencies for channeling

funds (for subsidies, turnkey fees and trainings) to grassroots NGOs.

The technical support was provided by a national level technical support

organisation, who had developed the popular Deenbandhu biogas plant.

This programme was conducted through AIWC branches in various states

as well as other NGOs as partners.

AIWC had conducted more than 15-20 day bio-gas training programmes for the construction and maintenance of bio-gas plant and built over 10,000 plants.

- One of the branches of AIWC at Chunar, which is half way between Varanasi and Mirzapur in the state of Uttar Pradesh is working with nearly 800 women belonging to Self Help Groups (SHGs) providing training in various income generating trades like carpet weaving, pottery making, etc and employing them.

- This branch had taken up the AIWC NPBD programme and had implemented a very successful biogas dissemination and implementation programme, constructing 300 biogas units in this area. Since women were directly involved in this programme even after four years of implementation almost all the bio-gas units are being used by the end users, which has also created very big demand for construction of bio-gas plants.

- The husband of one of the beneficiaries “Laxmi” was running a poultry farm where they had around 150 birds in the big terrace in their house and through AIWC biogas programme they had built a 4 cum capacity unit in their backyard, which were fed with poultry litter and producing substantial quantity of bio-gas every day to all the needs of a joint family of 15 as well as their poultry farm workers. The pressure of gas was so high that at times they had to release the excess biogas it to reduce the pressure.

- Laxmi was happy with the biogas as now she doesn’t have to use any other fuel in her house for cooking, but it has become a source of additional income for her, as she started supplying bio-gas to 6 to 7 houses nearby and charging them for the gas. She also had more surplus time and started working with AIWC branch at Chunar, which started giving her more self confidence. With the improvement of health due to reduction in indoor pollution as a result of use of biogas as a clean fuel for cooking, her standard of her life also improved, leading other women of the self-help group to follow her example, which created good positive impact on the socio-economic situation of the women in Chunar.

A group of women who are members of self help group (SHG) run by our partner NGO in Kakinada in Andhra Pradesh state have got their biogas units constructed under the AIWC bio-gas programme by taking the loans from their respective SHGs or building biogas. They have returned the entire loan with interest and are happily using their biogas, for cooking, lighting, and using the biogas digested slurry for their kitchen gardens and agricultural fields. There is great demand for more biogas units.

AIWC experience had been that wherever the women of the house had been trained in the use of biogas the correct way of feeding, maintaining etc. the units are always working well since the women have understood the importance & the benefits of using these bio-gas units. These two examples demonstrate that women SHG could provide one of organizational solutions for the effective means for promoting any affordable rural oriented RETs.

4.5

Village/User Cooperatives & Societies-

Denmark experience that can be applied in South Asia

With cooperatives people are able to do things that they could not do

alone. They can buy, sell, and process

food and materials on large scale. They can employ people with skills

they need. They can become independent

of suppliers or services they find inadequate.

During the last century cooperatives have been crucial for the successful

development of many of the richest countries of the world, such as the

Danish farmer cooperatives that helped to establish Danish agricultural

exports (Denmark is today the fourth richest country per capita).

Cooperatives can be crucial for activities that private investors will

not invest in because the profits are too small.

The main types of cooperatives are:

-

consumer cooperatives, where consumers own their shop, electricity provider, water supply etc. together (in some countries called consumer societies)

-

producers' cooperatives, where farmers sell their products together, own diaries together.

Cooperatives

are company structures, not social structures. They can involve poor

people and make their development easier, but

they do

not necessarily bring new resources to end poverty.

In a cooperative each member pay an entrance fee (share) according

to his or her needs for the service the cooperative provides

and sometimes additionally gives a guarantee. Then the members

can use the service

and pay or receive money depending on the kind of cooperative.

The cooperatives

are either non-profit companies or pay their profit to the

members of the cooperative according to the share or the actual

use of

each member.

Often cooperatives are limited companies where the members

can never loose more than their share + their eventual guarantee.

In cooperatives

the general rule is that each member has one vote.

Cooperatives have been important in development of energy supply, owning power plants, electric grids and many other supply structures that a family or a small company cannot afford alone. This is the case in many countries of the world. Energy cooperatives to reduce poverty can include:

- Village cooperatives that establish small hydropower & mini grid (see case from Sri Lanka).

- Village cooperatives to establish local power supply e.g. from wood gasification, engine, PV.

Consumer cooperatives

for maintenance, such as repair of PV and biogas installations.

Consumer cooperatives

for maintenance, such as repair of PV and biogas installations.- Farmer cooperatives that produce vegetable oil for transport (e.g. Jatropha oil) or bio diesel.

- Farmer cooperatives that produce fuel (e.g. charcoal briquettes) from agricultural residues.

To work successfully, cooperatives must be adapted to the societies

they are part of and they must have the necessary skills

and facilities for

the types of businesses they are doing. In addition they

must have a leadership and a board of members that actively

work for

an efficient

operation of the cooperative aiming at the highest benefits

for the members.

Like any other business, cooperatives are not free from

problems. Problems to look out for are:

-

That the cooperative work as efficient as a good private company

-

That the management does not take private benefits from the operation or give special benefits to some people. This has been a serious problem in areas where there is little experience with cooperatives or where the business morale for some reason degrades.

-

That the conditions for the cooperative can change so much that the benefit of the cooperative for the members does not exist any longer. Then a restructuring is necessary, based in an analysis of the development and of the opportunities, and a general discussion among members.

-

Dissatisfaction among members. To avoid that, cooperatives must have the maximum openness in its operations. Members must know precisely why they pay for. Further, they must have opportunities to suggest improvements.

How to form a cooperative:

-

First there must be a need for the service that a cooperative can provide (such as lack of rural energy supply) and ideas to solve it (such a local energy supply)

-

An overview of available legal structures is important, and then to choose the best available option (few lines about available structures in the four countries, such as the structure “limited cooperative” when it exist)

-

A business plan that makes it clear to potential members what they get, what they pay and what they risk. The business plan should be based on best available information including experience from similar activities, eventual subsidies that can be given, etc.

-

Information to potential members

-

Creation of a list of interested members. Usually the cooperative can only be established if a minimum number of members join.

-

Bylaws should be developed, usually based on existing bylaws from similar cooperatives

-

A general assembly is the formal start of the cooperative. It also elects the board that starts the operations.

4.6

Decentralised Power Generation using Solar PV system in remote

Non-Electrified area, Operated and Management by Producers-cum-Consumer

cooperative- A case of Sagar Island, India

Sagar Island is a large island with an area of around 300 sq km spread

over 43 villages and a population of over 1.60 lakhs, situated 110 km

south of Kolkata. One of the main problems of the people of Sagar Island

had been non-availability of grid electricity. Till 1996, there were

only a few Diesel Generating sets with total capacity of 300 kW were

providing electricity to a few selected 400 consumers, and too for a

few hours in the evening. The operation and maintenance requirements

of these generators were quite high and at the same time causing adverse

environmental pollution.

In 1996, Sundarban Region was identified by MNES as one of the high priority

area under its Solar Photovoltaic (SPV) Programme and gave necessary

funds to WBREDA (West Bengal Renewable Energy Development Agency) for

setting up of SPV Power Plants there.

As a result of MNES funding, in February 1996, the WBREDA set up and

commissioned the very first 26 kWp SPV Power Plant at village Kamalpur

in Sagar Island, with only 19 consumers.

At present many such power plants with aggregate SPV capacity of 300

kWp are in operation in Sagar Island providing electricity to around

2,000 households. These Power Plants have been set up with financial

support from the MNES and the State Government, as well as soft loan

assistance from the Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency (IREDA)

under the World Bank assisted SPV market development programme.

At present many such power plants with aggregate SPV capacity of 300

kWp are in operation in Sagar Island providing electricity to around

2,000 households. These Power Plants have been set up with financial

support from the MNES and the State Government, as well as soft loan

assistance from the Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency (IREDA)

under the World Bank assisted SPV market development programme.

At present, more than 50% of the total electricity consumed in Sagar Island is provided by solar energy generated electricity, through SPV systems, which also includes operation of essential services, like hospital services, water supply, etc.

The unique Features of SPV Programme at Sagar & Moushuni is that these SPV power plants are being run on commercial mode through the local rural co-operatives formed by the beneficiaries themselves under the aegis of WBREDA, catering to both the domestic & commercial needs for 5-6 hours in the evening daily. For obtaining a connection from the power plants, the end-user, is required to pay Rs.1,000/- as connection charge. Thereafter, each household (end-user) pays a monthly charges, ranging from Rs. 130/- to Rs. 1,300/-, which depends upon the connected loads, which are in the range of 100 to 1000 watts.

The distinguishing feature of the SPV decentralized power programme in both Sagar as well as Moushuni islands is the integration of power & water supply systems in these projects. The power plants have been designed to operate low cost conventional water pumps of average 3 HP capacity with an intelligent controller during daytime to provide drinking water without incurring any extra cost, except installation of some additional SPV modules. Around 700 families are getting the twin benefits of such integrated power & water supply systems at present in the twin Islands of Sagar and Moushuni.

This decentralized power generation venture utilizing SPY system, has opened up a new opportunities for meeting two basic needs of electricity and water together, of the dispersed population of the isolated & remote habitats having no alternate or traditional energy sources, in a meaningful way.

4.7

Village Hydro Power Consumers’ Societies

in Sri Lanka

In Sri Lanka, 65% of households have access to the national electricity

grid. Majority of the rest use kerosene for lighting. Within the next

10 years, the total electrified may reach 75% of households. The government

has implemented the renewable energy for rural economic development

project (RERED) with the support of the World Bank and UNDP (GEF).

This programme is implemented to promote the use of micro hydro, photovoltaic

or biomass in households not serviced by the national grid. The main

component of this project is a credit programme to provide medium and

long-term financing for private project developers, NSOs and community

cooperatives, so that the household electricity can be provided by

renewable energy options. The project runs from 2002 to 2007.

Under this programme it is planned to install 90 schemes with a total

capacity of 3762 kW ranging from individual capacities of 2.6kW to 40

kW to provide electricity to 3762 households. At end of Dec 2004, 31

micro hydro schemes were completed providing electricity to 1979 houses.

The rest of the projects are in progress. At present it is estimated

that nearly 250 off grid village hydro schemes are in operation in Sri

Lanka.

Under this programme it is planned to install 90 schemes with a total

capacity of 3762 kW ranging from individual capacities of 2.6kW to 40

kW to provide electricity to 3762 households. At end of Dec 2004, 31

micro hydro schemes were completed providing electricity to 1979 houses.

The rest of the projects are in progress. At present it is estimated

that nearly 250 off grid village hydro schemes are in operation in Sri

Lanka.

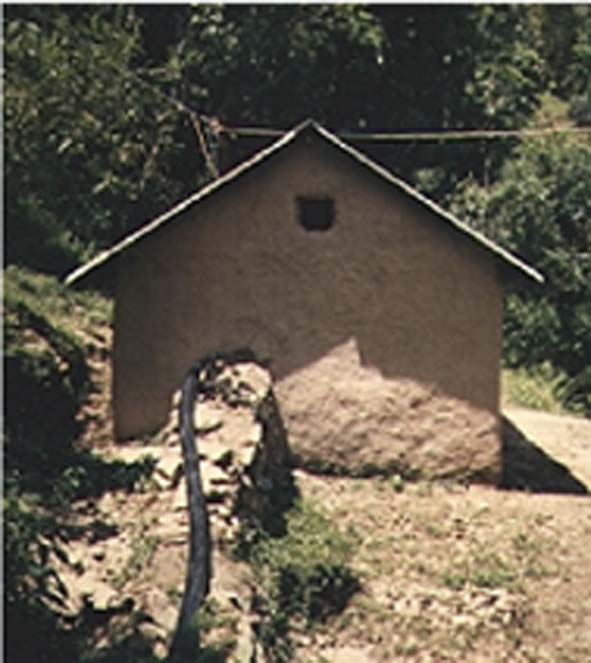

One of the villages covered under this programme is "Waturawa" is

a small village with a population of 250 people living in 45 houses situated

in the Ratnapura District famous for gems in Sri Lanka. It is 10 km from

the closest town and accessible by public transport. The main occupation

of the villagers is agriculture. The national electricity grid is 4 km

away and it is unlikely that the grid will be extended within the next

two decades.

The main energy sources

in the village are firewood for cooking, kerosene for lighting and

few using car batteries

to watch TV. Each household

spends about Rs 500/month to meet the energy needs. The village receives

an annual rainfall of 4000 mm. The terrain of the village is hilly and

a perennial stream runs through the village. This stream was exploited

to provide electricity to the village. Since the houses are scattered,

only 25 houses could be electrified. The electrification was carried

out by IDEA as the project developer under the RERED programme.

After careful sensitization and building confidence of the village members,

a consumer society was formed. The office bearers were trained to take

on the appropriate responsibilities to run the project on a sustainable

manner. Feasibility study and loan documentation were completed by IDEA.

Processing of the loan took about 4 months.

After confirmation of the loan, each household was expected to contribute

Rs 4000 (33 Euro) initially to the society funds and provide labour services

on a voluntary basis in the construction of civil works and distribution

lines. The electrical and mechanical equipment were made by local manufacturers

trained by the ITDS. All unskilled labour for the civil works was provided

by the members and carried out under the supervision of IDEA. The society

was able to secure Rs 200,000 from the provincial council to meet the

initial cost. The construction work was completed within a period of

nine months. The society charges a fixed monthly fee of Rs 600 (5 Euro)

from each household for the use of electricity. It is virtually the loan

component payable by the society/member to the bank. The loan was released

by the bank after the certification provided by a chartered engineer

appointed by the bank, that took nearly six months after completion.

The grant of SL Rs 400,000 obtained under the RERED project was invested

in a bank and the interests received is maintained as a separate fund

to meet the cost of maintenance and operations.

The society has managed the scheme in a very good manner for the last

two years. There has been enough water throughout the year for continuous

operation despite the drought conditions experienced in the dry season.

The power generated is used mostly for lighting, ironing and watching

TV. All the 25 houses have colour TVs and electric irons and refrigerators

in 4 houses. Initially only CFL lamps were allowed but fused CFLs are

often replaced with incandescent lamps due to high cost. Members are

however requested to avoid the use of incandescent lamps, heating equipment

and refrigerators during peak hours. During the day time the power is

supplied to a 1.5 HP chili ginding mill.

The only major problem encountered has been the flooding of the power

house, which costed Rs 20,000 for the repairs of the electrical equipment.

4.8

Micro-utility Model in implementation of Solar PVS by Grameen Shakti

in Bangladesh

Only 30% of the Bangladeshi people have access to grid electricity and

most of them live in the cities. There cannot be any economic development

without electricity. Because of this, rural communities suffer from under-utilized

economy and depressed business activities. Mobility of people is also

hampered after dusk due to security problems. However many people cannot

afford Solar Home Systems individually. This is one of the barriers to

the scaling up GS solar programme and revitalizing rural economy through

the use solar PV technology, that many people cannot afford Solar Home

Systems individually.

The Grameen Shakti’s “Micro-utility model” Solar Energy

Programme has been initiated to address these vital issues of extended

business hours for increasing business turn-over. The GS’s “Micro-utility

model” scheme is meant

GS has therefore, developed this special programme to make it easier

for those who cannot afford SHSs individually and to become owner of

one. Under this programme, GS facilitates a group of people to share

the cost and benefit of using a Solar Home System (SHS). This programme

is based on ownership model because this ensures individual responsibility

The purchaser of the SHS is considered the owner of the system and is

responsible for re-paying installments to GS. The due amount is paid

to GS by renting his lights to other people especially to his/her neighbours.

This scheme especially targets the petty shop keepers in rural and semi

urban areas, which are not connected with grid electricity.

GS took up an intense promotional campaigning among the shopkeepers to

popularize this model. The GS also developed an attractive package to

create interest among the shopkeepers community to make them owners of

SHSs under this model.

Under this scheme, the entrepreneur

or the prospective owner of SHS does not have to pay any service charges

and gives a small initial down

payment of only 10% and gets his SHS installed. By regularly paying his

installment, he would become the owner of the SHS in three and a half

years. This strategy yielded the amazing results and thus Micro- utility

model has become extremely popular among the shopkeeper’s community.

Till date, more than one thousand SHS’s have been installed under

this scheme. This model of implementation has helped GS to tie solar

PV technology with income generation, thereby bringing the greatest benefit

to its end-users. This has also helped GS to scale up its programme by

reaching those who cannot afford a SHS individually- GS has thus able

to install more than 2000 SHSs.

One such shopkeeper Mr. Umor has a grocery shop at Kormal bazaar. He

has bought a solar home system with six lamps. He is using one lamp himself

and renting the other lamps to neighbouring shops for a fee of 7 cents

per night/ lamp. In this way he has increased his income and the income

of the neighbouring shops.

The growing and striking impact of Micro-utility model is that it has

increased business turnover and extended business hours in rural bazaars.

Now shopkeepers can afford pollution free, efficient lighting at minimum

costs and keep their shops open after dusk- thus more business. Customers

also enjoy greater mobility- freedom and can come to the markets after

dusk.

Micro-utility Model in a market place

There is reduced health risk and less danger of fire because kerosene lamps are not being used. Women also enjoy greater mobility and freedom because their security is increased due to better lighting system. The applied technology is highly upgraded one but easy and people friendly. After making full payment, there is very little additional cost involved. The capital cost of SHS is recovered in 3-4 years. Lighting is available for almost 4 hours per day.

4.9

SPV Lanterns for Mobile Stall by Poor Couple Food for Income Generation,

AIWC, India

Elliot Beach in Chennai.-Madras The “Other” beach of the

city– as against Marina, to the north is becoming increasingly

popular as the evening destination of the people, especially from the

nearby residential areas, Of late, a number of small stall have sprung

up, which function in the evenings, from about 6 pm to 10 pm selling

small eats- chilly cutlets, wafers, etc, and some offering amusements

like shoot the balloon, darts etc. In the beginning about 20 of these

stalls used solar lanterns.

Chandran and his wife, who are residents of a nearby fishing village,

run a vegetable cutlet stall. They have two lights which they take from

a nearby house. An enterprising person there had purchased about 24 Solar

lamps, takes an advance of Rs. 100/- per light and Rs. 10/- per light

per day after 10 pm they return the lights to the owner who gets them

charged for the next day, keeps them ready for use in the evening.

Chandran and his wife make about Rs.50 to Rs.75 on week days and Rs.100

to Rs.150 on the evenings of week-ends. They have no problem in paying

the one time deposit of Rs. 100/- and the daily charge of Rs.10/-per

light. They say the Solar lamps give light for a little more than 4 hours

and functions well, which is enough for them. They do not have to buy

Kerosene for the petromax lights they were using earlier, and they don’t

have to buy those lights or spend a lot of time cleaning them. Their

hands also used to smell of kerosene, which was not relished by the customers!

And the solar lights are not “hot” to remain closer to it.

They are very happy with the solar lights. It not only prevents kerosene pollution on the beach but also proves profitable to the enterprising persons who rents them out on daily basis. Now 3 years later there are hundreds of Solar Lanterns being used along the beach and it is a beautiful sight to see in the evenings.

4.10

Role of Rural Energy & Ecological

Volunteers Corps (REEVOCs) in RE promotion India

The village level volunteers group, called as REEVOCs (Rural Energy

and Ecological Volunteers Corps) has played an important role in the

implementation

and management of renewable energy (RE) programmes in 12 Eco-villages.

These villages are being jointly promoted and developed by WAFD and INSEDA

under the “eco village development projects”, since April

2002.

The last 4 ½ years of experiences in the “eco village development

project” has shown that unless a community has ownership of a programme

and is involved at all levels from planning, implementing, monitoring

and evaluating, long term sustainability is not possible. The EVD project

being implemented in 12 villages of Sewar Block in Bharatpur District

of Rajasthan state, has successfully demonstrated this.

The steps followed in this process are summarized below:

- A group of 4 volunteers were selected from each village, 2 men 2 women making a total of 48 volunteer group, called as REEVOCs

- For 2 years this group (entire 48 volunteers) met at least once a month and learnt about the importance of eco village development and it’s relevance in today’s world, and the important role that renewable energy plays in this; and

- It is important to target each important group in the village, to achieve this, these volunteers helped promote and organize, in their villages, women’s groups and youth groups, and carried out implementation and demonstration of among other things renewable energy units.

After four years of implementation these volunteers (REEVOCs)

have understood the importance of eco village development,

and the role

of renewable

energy such as biogas plants, plantation of energy crops

like Jatropha, and solar energy. In addition they have

also become

aware about the

production of SVO (straight vegetable oil) and bio diesel

from non-edible oil seed

like Jatropha seeds for operation of diesel pumping sets,

as well as decentralize power generation at the rural

household and village

levels,

by using bio-diesel operated generating sets. They are

now motivated to undertake Jatropha cultivation on the boundaries

and their other

wise unproductive waste lands.

Now for more systematic and organized implementation of

RE and other related activities in an integrated manner

for

desired output/results

in a foreseeable future, the 48 REEVOCS have formed a “management

committee”. This “management committee” has been elected

by the volunteers themselves which has one representative from each of

the 12 project villages. The management committee in tern has elected

6 office bearers- out of them three are the key office bearers, i.e.,

President, Secretary and Treasurer, to oversee the day to day operation

aspects of the programmes in these 12 eco-villages. The other office

bearers are, Vice president, Joint Secretary and Joint Treasurer. The

office bearers take more responsibilities on behalf of the management

committee and meet more frequently during the inter-sessions of the management

committee meetings and are delegated to meet the district level government

functionaries to present the problems of the group as well as find out

appropriate government programmes to implement in these 12 villages.

Now for more systematic and organized implementation of

RE and other related activities in an integrated manner

for

desired output/results

in a foreseeable future, the 48 REEVOCS have formed a “management

committee”. This “management committee” has been elected

by the volunteers themselves which has one representative from each of

the 12 project villages. The management committee in tern has elected

6 office bearers- out of them three are the key office bearers, i.e.,

President, Secretary and Treasurer, to oversee the day to day operation

aspects of the programmes in these 12 eco-villages. The other office

bearers are, Vice president, Joint Secretary and Joint Treasurer. The

office bearers take more responsibilities on behalf of the management

committee and meet more frequently during the inter-sessions of the management

committee meetings and are delegated to meet the district level government

functionaries to present the problems of the group as well as find out

appropriate government programmes to implement in these 12 villages.

The role of this management committee is to sit with WAFD and take an active part in planning, implementation, evaluation and monitoring of the programmes, which will have focus on community-centered poverty reduction, by integrating REs in all the socio-economic developmental programmes. Field level monitoring and decision-making is done much more effectively by the committee. Solutions to problems are found by the committee jointly, which are cost effective as well as much more realistic and field oriented.

Role of WAFD is that of a facilitator and to for providing guidance

where needed, as well as to arrange for funds, training, RE, demonstration

and mobilize appropriate technical support.

To further ensure people’s active participation, self help groups

or user groups and micro-credit groups are being promoted for different

activities, such as user group for bio gas plant owners, user group for

kitchen gardens etc. These user groups will further help the managing

committee in monitoring, evaluation and promotion of their specific programs/activities.

To sum up, village level

management of programmes through people’s

own committees and organizations will ensure sustainability and continuity

of the programme.

Over time a knowledge bank will be created within the people themselves,

and they can take care of most of their problems. External dependence

will be reduced in terms of dissemination of new findings and information

etc, from time to time.

With experience the group will be able to independently access certain

funds from government and other sources as well.

4.11 Role of Private Sector in the Promotion of Sustainable Energy Technologies

in Nepal

Nepal is a mountainous country with rugged terrain and several perennial

streams, rivulets and rivers. In the mid and high hills of the country,

Traditional Water Mills (TWM) or Ghattas, are located on the banks of

these water sources that– for centuries- have been part of rural

communities and are used as an important energy source for grinding cereals.

As per an estimate 25,000 to 30,000 mills are in operation in the country,

one unit typically servicing 20- 50 households. Because of their low

efficiency, the traditional water mills are hardly able to cope with

the increasing food-processing needs of the local communities, resulting

in to their place is be taken over by the diesels powered mills, and

to a lesser extent micro hydro mills. These modern mills are neither

environmentally benign nor sustainable as they use imported machinery

operate on diesel fuel, which drains the countries foreign exchange and

creates atmospheric pollutions.

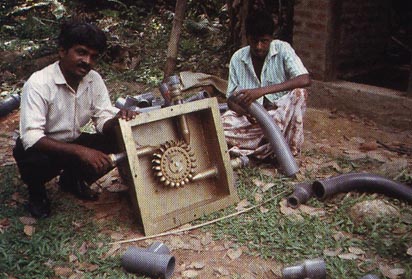

An Improved Water Mill (IWM) has been developed that has almost double

the efficiency of the traditional water mills and also improves performance

as well as reliability without changing the traditional management system.

The improved water mill technology is a modified version of the traditional

water mills designed on the principals of Impulse Turbine.

An Improved Water Mill (IWM) has been developed that has almost double

the efficiency of the traditional water mills and also improves performance

as well as reliability without changing the traditional management system.

The improved water mill technology is a modified version of the traditional

water mills designed on the principals of Impulse Turbine.

The technology has a direct impact as it can be used for a longer period

into dry season and- through their increased energy output- the quality

of the milling services offered to the local community improves. The

improved service quality is translated into a higher agro processing

capacity (milling capacity often doubles) and/or diversified range

of services (hulling, oil expelling, saw milling etc). An IWM also

generates electricity for remote villages contributing to the quality

of their livelihood.

The history of IWM development in Nepal dates back to 1984, when the

German Appropriate Technology Exchange of the German Technical Cooperation

(GTZ/GATE) initiated a programme aiming for dissemination of IWM. From

1990 onwards the Centre for Rural Technology, Nepal (CRT/N), with the

assistance of GTZ and other development organisations, has actively involved

in the promotion and dissemination of IWM through supporting traditional

Ghatta (Water Mill) owners for improvement.

IWM Program has adopted approaches that lead towards making the program

sustainable. It has emphasized for active collaboration and participation

of private-public sector partnership on the basis of their comparative

advantage regarding different aspects of the programme.

The focus has been given for the effective institutional linkages among

the program partners such as Centre for Rural Technology, Nepal (CRT/N)

as implementing agency, Alternative Energy Promotion Centre (AEPC), the

government’s wing for the promotion of alternative energy and executing

agency of IWM program, SNV/Nepal representing the donor, development

organizations involved in the promotion of the technology, Service Providers,

Water Mill Owners and its Users.

The private sector organizations, including the NGO has been playing

key role in the effective delivery of quality services for the promotion

and dissemination of the technology in Nepal. Major private organizations

involved for the delivery of various services in the programme are as

follows:

-

CRT/N is the lead organization responsible for the implementation of the whole programme. Within the framework of the programme, CRT/N has worked closely with government agencies, donors, development organizations, I/NGOs, private sector organizations and service providers etc. for its smooth implementation.

-

IWM Service Centres are private sector entity, pre-qualified by the programme to work at the local level, and are key actors in delivering socio-technical services required by the mill owners. Presently 16 IWM Service Centres are working in 16 districts, one in each district. They are responsible for inventory of water mills in programme districts, social mobilization, Water Mill Owners' Group/ Association formation, Orientation/Demonstration organization, feasibility survey, procurement of IWM components from manufacturers, linking with micro-financing institutions to facilitate credit support to interested mill owners, installation of IWMs and providing after sale services.

-

Private workshops and manufacturers are responsible to produce standard kits suitable for various end use purposes as per required by the mill owners. Presently there are 8 manufacturers pre-qualified by the programme for ensuring the supply of quality products. The quality of the products is checked and controlled by CRT/N.

-

The Micro-finance Institutions (MFIs) are also key players, responsible basically to administer credit support to interested mill owners in coordination with IWM Service Centres, though MFIs are still not so organized on the delivery of required credit to the millers. Therefore, at present, the IWM installation is mostly done through self-financing by the millers themselves with some subsidy support for the installation activities.

-

Water Mill Owners' Association works mainly as a pressure group for the rights of the mill owners and for awareness campaign among the millers and users not only for IWM promotion but also for social and income generating activities linking with other renewable energy. Some associations are also working as IWM Service Centers and MFIs

-

Local Blacksmiths are available at the local level for the supply of spare parts required for regular repair and maintenance of the technology.

-

There are institutions that undertake various programmes related trainings, studies and assessments, publication related works etc. Their role has been useful in the local capacity building through skill and entrepreneurship development and potential end use diversification.

All the private partners have been playing their respective role in an effective manner to make the programme a success. But all the key actors are inter-dependent for effective delivery at the end users level. Sketch below highlights the institutional linkages of private- public sector collaboration:

4.12

Solar Home Lighting (SHL) through Women’s SHGs in Alwar dist,

Rajasthan, India, by SOHARD

Balaheer village belongs to Neemrana block, and lies to the north-western

corner of Alwar district in Rajasthan. Balaheer is a part of the neighbouring

Nangli village, hence popularly known as Nangli Balaheer. It’s

a medium-sized village having a population of 850 people.

Electrification of Balaheer village was a distant dream that meant acute

problems for the community due to lack of power and electricity supply

resulting in numerous problems and more so for the school going children

and women.

SOHARD has installed a total of 44 solar lighting systems to 44 families

on equal financial partnership with the SHG’s. Following strategy

was used for implementation, which led to success:

-

Focused on rural women, especially of deprived and marginalized sections of the society.

-

Rapport building with the village community, through active collaboration with the women Self Help Groups (SHGs).

-

Ensuring community participation in the programme by motivating and convincing them to contributes at least 50% share from the villagers for the purchase of SHL system.

-

Devised proper mobilization- education, capacity building processes and follow-up mechanism for minimum one year for analyzing success and sustainability of the Project.

Providing the solar home lighting system (SHLS) through SHG’s has resulted

in empowerment of the women members of SHG, who were completely involved in the

process. Some of the direct benefits of the SHLS provided to SHG members were

improved performance of their children in studies, due to un-interrupted and

pollution free lighting systems during the night, generation of additional income

Solar Lighting Lamp project progressed due systematic mobilization of people

at the village level and their active participation.